To make health premiums affordable, CT must address input costs

Health benefits in Connecticut are costly and rising faster than inflation. Last year, total employer-sponsored health insurance premiums in Connecticut were the sixth highest among states for both single and family coverage. Connecticut workers paid 7.8% more for single coverage and 4.3% more for family plans than other Americans.

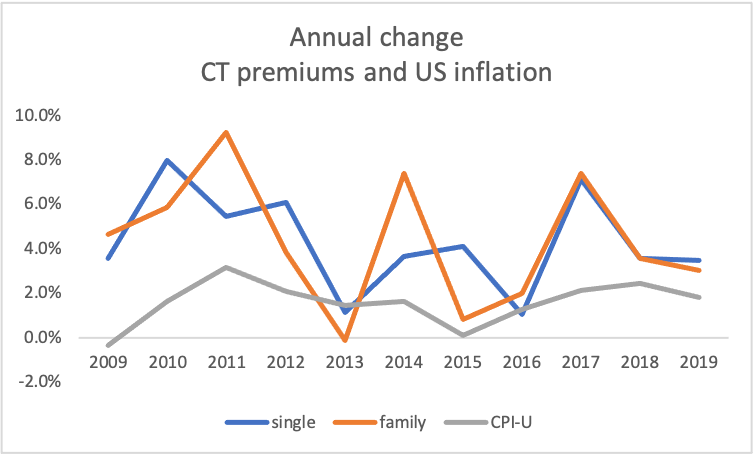

Although Connecticut premiums are rising more slowly than other states, they are growing far faster than the rate of general inflation. Between 2008 and 2019, both Connecticut single and family plan premiums’ average annual increase was 4.3% Over those same years, US consumer prices averaged only 1.6% increases annually. Similar cost increases into the future cannot be sustained by Connecticut’s households or employers.

To lower the cost of premiums, Connecticut must look under the hood and address health insurance’s input costs. Addressing the underlying drivers of rising health costs will make healthcare premiums more affordable in a sustainable way.

Prices are driving premium increases, both nationally and in Connecticut. Specifically, increasing prices for prescription drugs and for inpatient and outpatient services provided by large and growing healthcare systems in our state are the main contributors to increased healthcare prices.

Other states are not waiting for federal help and are addressing these cost drivers. Connecticut has several policy options available to address rising prescription drug prices and the cost impact of health system consolidation.

Prescription drug costs

Connecticut residents spend more per person for prescription drugs than residents of any other state. Drug costs are growing faster in Connecticut than other healthcare sectors and faster than the rest of the country. Other states have taken the lead in controlling drug costs.

A promising option that avoids lawsuits and other challenges, is imposing penalties on companies that increase prices on existing drugs without justification. There has been great public outcry about drug company profit-taking on existing drugs without reason including insulin, epi-pens, and Martin Shkreli and Deraprim. Increases on prices of existing drugs far above medical inflation rates without research supporting enhanced effectiveness or economic benefit, new uses, or large increases in production costs, is a major driver of rising drug costs for states and insurers.

In 2018 and 2019, unjustified price increases for seven existing drugs cost the US health system $4.8 billion.

Unsupported Price Increases, ICER

Massachusetts is proposing to impose penalties on drug companies with excessive price increases in the state. Under H.41334 the state will investigate drugs with price increases that exceed medical inflation by more than 2% to compare the new price with the value of the drug, using comparative effectiveness analysis. If the price is excessive, the company will be assessed a tax equal to 80% of the excessive amount of the price for each unit sold in Massachusetts.

It is important to note that Massachusetts has a sophisticated, and well-resourced, commission capable of performing the analysis and a mature, functioning All Payer Claims Database for the analysis. Connecticut has neither of these resources.

Other states are pursuing the same goal using analysis of price increase justification by an independent, privately-funded nonprofit, the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER). ICER is the national leader in evidence-based evaluation of the value of medical treatments, including drugs. All ICER reports, and supporting research, are public. ICER’s many analyses are used by over 75% of private health plans and Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), the US Department of Veteran’s Affairs, Medicare plans, and state Medicaid programs. ICER engages with over 300 patient groups to ensure real-world evidence is included in all their value assessments.

In response to requests from state policymakers and other stakeholders, ICER publishes annual analyses of unsupported price increases for drugs with high spending levels not justified by new evidence of effectiveness, economic benefit, or increased production costs. The first report, published last year, found that price increases for seven of nine drugs with substantial price increases in 2018 and 2019, were not supported by the evidence. The seven drugs cost the US health system an additional $4.8 billion over the two years. Humira led the list with unsupported price increases costing an extra $1.9 billion. ICER’s next report is due to be released in January 2021.

The National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP) has developed materials and legislative language for states to use ICER’s report to lower excessive drug price increases for all payers. The language creates a tax penalty similar to Massachusetts’s and directs the funds to lower consumer costs of insurance. Legal experts expect the language to withstand court challenges. In contrast to earlier proposals, the current option does not require states to devote resources to a Drug Affordability Review Board. The bill has been filed in Washington state and more states are considering it.

Health system consolidation

Mergers are the other major driver of healthcare costs in Connecticut. As health systems grow larger, competition suffers, and the systems can demand higher prices. Both horizontal mergers between large hospital systems and vertical mergers that combine hospitals, practices, and other provider groups, increase prices. Prices for a diverse array of healthcare services increase with mergers. Studies have found little or no benefits from consolidation in controlling costs or improving the quality of care.

Mergers also reduce consumer options for care and increase health system levers to keep patients within their network. Health systems have financial incentives to refer patients only to corporate partners for specialty and other care, rather than the best option for the patient. Patients may have to drive farther to get care from providers outside their community, with inconvenient hours, that don’t speak their language or share their culture, may not have experience or the best quality rating for treating their condition, and have to see a provider they don’t trust or aren’t comfortable with.

Consolidation of practices and hospitals into large health systems reduce competition, reduce consumer choice, and raise healthcare prices. There is no evidence that consolidation improves the quality of care.

There are concerns that financial losses facing hospitals and health systems because of the COVID pandemic will accelerate mergers and increase prices to recover those losses. There are powerful incentives for consolidation in federal law, including favorable drug cost policies and tax benefits of nonprofit status. However, newer federal policies on surprise billing and price transparency may help mitigate some of those advantages.

A year ago California’s Attorney General Becerra, now incoming US Secretary of Health and Human Services in the Biden administration, reached a historic anti-trust settlement with Sutter Health, a large health system. The state and several payers argued that Sutter Health used its dominant position in Northern California’s market to illegally drive up prices. Under the settlement, Sutter Health will no long use all-or-none contracts, requiring payers to include every Sutter hospital and clinic in their network, even if there are less costly alternatives in the community. The settlement also limits out-of-network charges to patients, requires full public pricing transparency, and ceases bundling services and products to offer stand-alone pricing.

Others have focused on restrictive covenants/noncompete contracts that health systems pair with large bonuses for providers to sign up. These contract provisions lock providers, and their patients, into the health system and lower competition. The bonuses are often funded through new facility fees on the practices’ patients. Those agreements are governed by state law.

Senator Looney, President Pro Tempore of Connecticut’s Senate, has proposed tightening standards for health systems acquiring practices as a legislative priority for 2021. Business leaders nationally have called for a moratorium on mergers, both horizontal and vertical, and creation of a task force to explore options to promote competition and control costs.

Connecticut could follow on these leads by implementing a moratorium on mergers and acquisitions until a public, bipartisan taskforce of independent experts can identify feasible, effective policy options to improve competition and consumer choice while minimizing unintended consequences.

Connecticut state policymakers can address premium input costs and make health care premiums more affordable, now and into the future.